STUDENT ACTIVISM: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

50 years ago: Anti-war movement comes to Skyline

This is the second in a series of three articles looking back at events at each of our three colleges fifty years ago as the anti-Vietnam War movement swept college campuses around the country. The first article, focused on Cañada College, ran in the May 2020 Advocate; a third article planned for 2021 will focus on student activism at CSM during 1967-1969. (CSM student activism during that period was also described in great detail by SF State faculty member Jason Ferreira’s article, “From College Readiness to Ready for Revolution!”)

by Jessica Silver-Sharp, AFT 1493 Secretary & Skyline College librarian

As we encourage our own students to speak out and take action for social justice, it seems timely to present a second article about the history of student activism in our district, this time at Skyline College, in the first year of its founding, 1969-70.

Even before the Kent State massacre on May 4, 1970, many Skyline students were voicing their opposition to US involvement in Vietnam, and of course, the draft. The first draft lottery was held toward the end of the college’s first semester on December 1, 1969; so male students entering Skyline in 1969 knew that once they graduated–or if they didn’t transfer within two years–they’d have to deal with the prospect of mandatory military service.

The killing of student protesters at Kent State had the effect of immediately mobilizing students across the country, including key groups of students across our three campuses, to join the largest student strike in American history at that time. In response to anticipated campus violence, Governor Reagan ordered classes canceled for four days, beginning May 7 (New York Times, May 7, 1970). Many Skyline students considered this an affront. In fact, defiant drama students continued on-campus rehearsals for Inherit the Wind, criticizing the Governor (and former actor) for throwing “the curtain down on academic freedom in California’s state and community colleges and universities.” (Skyline Press, May 13, 1970).

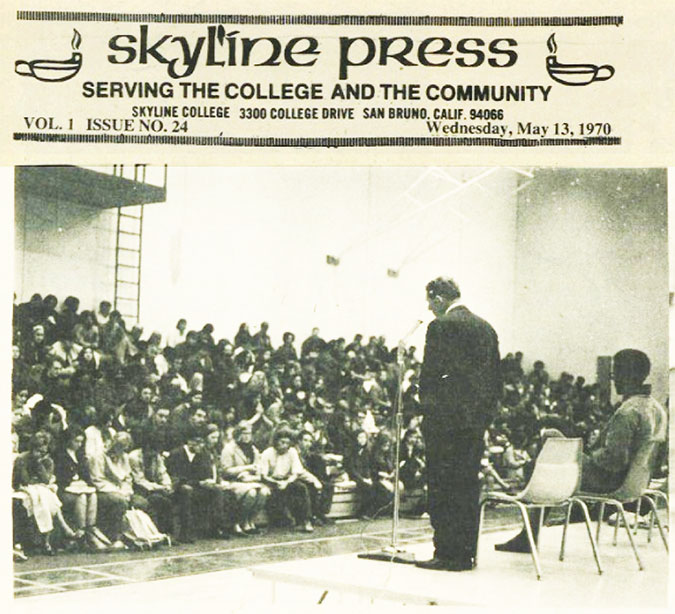

The class cancellations mobilized many students and faculty in the district. On May 6, according to the Skyline Press newspaper, Skyline students called a mass meeting. Skyline’s first president Philip Garlington attended and “Students for a Strike,” led by student Dan Tobias, urged the 600 plus students in attendance to begin boycotting classes once they resumed.

A mass meeting called by Skyline students on May 6, 1970, was attended by 600 including Skyline’s first president Philip Garlington

A mass meeting called by Skyline students on May 6, 1970, was attended by 600 including Skyline’s first president Philip Garlington

While no signs of pending violence appear in the reports, Garlington announced to the students gathered, “Violence on this campus isn’t a viable solution to the national problems facing us today.” (Skyline Press, May 13, 1970).

Anti-war message supported by Trustees and Academic Senate

Later that same evening, a group of “more than 500” students and faculty from all three campuses traveled to CSM where a televised Board of Trustees meeting saw “student and faculty spokesmen…demand[ing] to know what the board “as a governing body” was planning to do.” By the end of the evening the BOT presented a resolution, apparently prepared earlier in the day, “denouncing the national government’s policies in Vietnam and Cambodia…” (Skyline Press, May 13, 1970)

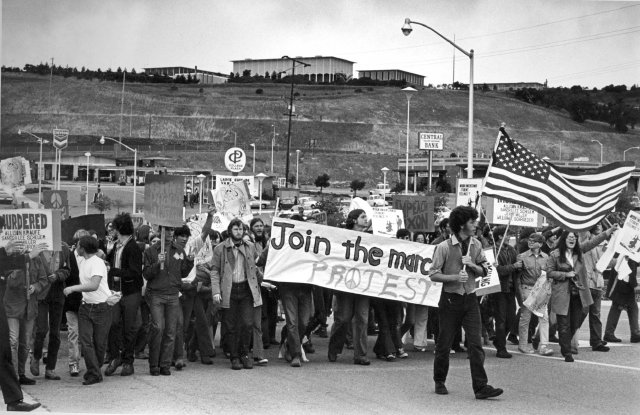

On May 7, with classes canceled but all three campuses apparently open, Skyline’s faculty senate passed their resolution of support: “We therefore support, in principle, the Skyline student strike to end that dedicated action may take place, both on the campus and extending into the community.” Students spent the day organizing. The next day, May 8, a contingent of Skyline and Cañada students joined a CSM student-organized peace march that was also attended by faculty. The march began at CSM and ended at San Mateo City Hall.

On May 8, 1970 Skyline and Cañada students joined a peace march organized by CSM students.

On May 8, 1970 Skyline and Cañada students joined a peace march organized by CSM students.

[Courtesy, CSM Photo Archives, Bill Rundberg]

Following the weekend, a May 11 memo by the Student Strike Committee announced their intentions: “We, the striking students at Skyline College DO NOT wish to shut down the college. Rather, we wish to re-direct it so that it may immediately become an EFFECTIVE INFLUENCE on the pressing international and social problems which are facing us today.” During the week of May 11-15, faculty held a teach-in style symposium with a published schedule of lectures taking place daily. An all-college memo on May 8 announced the schedule including “Mr. Yuman speaks on non-violence” and “A short film, Viet Nam — how we got in. How we can get out,” to be shown “every hour” on Friday.

Notably, the committee of striking Skyline students were respectful of the first ever Black Culture Week, organized by the first Black Student Union and also planned for May 11-15 but postponed until May 13, making sure that their events did not overlap.

Skyline students were split on whether to strike

Local newspapers reporting on this week and the week that followed indicate that perhaps more so than at Cañada College, Skyline students were split on whether to strike. It’s unknown how many students decided not to attend classes. The college’s Associated Student Body President Morrison Browne, a tall black student and a charismatic leader, urged in his speech that for the council to be successful “next year’s student council must fight apathy… and become more oriented towards political issues facing colleges.” (Skyline Press, May 13, 1970).

While it’s difficult to know how college administrators felt about the campus situation without existing interviews to draw from, their main focus was on preparing for the official college dedication on May 17, which appears to have gone off without a hitch.

More Questions than Answers

What were the effects of this early student and faculty activism at Skyline? To what degree were students influenced by the 1968 Third World Liberation Front Strike at San Francisco State? How many students and faculty were actually involved? How did these events in the college’s first year affect its course or emerging culture? A San Mateo Times article from November 1970 shows student strike organizer (then Student Body President) Dan Tobias appealing his expulsion from Skyline College. Were others punished as well? As is often the case, this initial research has perhaps raised more questions than answers.

Student Researchers at Work

At Skyline College, three honors students are examining the events of May 1970 with a goal of putting Skyline on the University of Washington’s “Strike Map” (where you’ll find Cañada College) as well as raising consciousness among their peers, and of course, learning to use primary sources for historical research. Perhaps they will draw some parallels to today’s protest movements as well. With interviews planned and more sources turning up every week or so, the students will report more information later in the semester in the form of student newspaper articles and research papers.

What Do You Know?

With libraries and archives closed during COVID, and early Senate records and Board of Trustees minutes not accessible (or location unknown), access to archival sources has been very limited. If you have information or knowledge of sources that can shed light on the Skyline College student strike of 1970, please share. If you have students interested in researching this topic, you may direct them to this library research guide, in progress, where sources and information are being collected. I’m also available to support students from any campus in their research.