May 2015 Advocate – Remembering Rudy Lapp

EMERITI REMEMBERED

CSM Ethnic Studies library dedicated to Rudy Lapp, CSM history professor from the 1950’s to 1980’s

By Al Acena, CSM Emeritus Professor and Dean

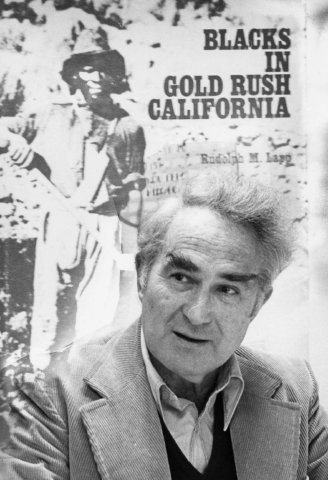

On April 2, 2015, the Rudolph M. Lapp Reference Library was dedicated on the 4th floor of Building 10 in the Ethnic Studies Department office. The library memorializes Rudy Lapp (photo, below left), who came to College of San Mateo in 1955, a newly minted Ph.D. from Berkeley. Rudy passed away in May 2007, and now a significant selection of Rudy’s books has found a  permanent home on CSM’s campus.

permanent home on CSM’s campus.

The library is a fitting tribute to Rudy as a book-hunter-and-gatherer, a trait he shares with a lot of historians. His fascination with books and reading went back to his early years and continued through his life, to the extent that he had to add an extension to his home to accommodate his book collection. At Cal, he became friends with a fellow grad student in history, Bob Burke, who was also a book collector and a student of the historian of American Populism, John D. Hicks. The book-hunting talents of these two came to Hicks’ attention. (Hicks was then writing a volume on America in the 1920s to be entitled “Republican Ascendancy.”) Rudy and Bob scoured used bookstores and libraries in Berkeley, Oakland and the East Bay for books helpful to Hicks. Their book-hunting efforts were noted in Hicks’ memoir, My Life in History. Rudy’s interest in libraries and books led to his service on the Library Commission of the City of San Mateo in the 1970s and 1980s.

Other notable CSM Social Science faculty

Some social science division faculty at CSM had gone on to teach at distinguished universities: Joan Hoff Wilson (Indiana University and executive secretary of the Organization of American Historians), Ronald Takaki (UCLA, Berkeley), Jack Atthowe (Rutgers, psychology department chair), David Lynn (UC Davis). Rudy made his entire professional career at CSM as a teacher/scholar. He made others in academe aware of CSM through his reviews, articles and books. Thus he brought luster to CSM as an academic institution.

Rudy’s most celebrated effort has been Blacks in Gold Rush California, published by Yale University Press in 1977, and it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in history for 1977 (the prize instead went to Stanford’s David Potter). It also received the California Historical Society’s Award of Merit for 1979. Rudy’s book did not just focus on blacks in the gold fields of the Sierras, but also on the social hardships they encountered in a “Free State” and the legal, educational and political obstacles they faced. Lapp’s achievement, simply put, was to take a human story – black migration to California at that time – and give it a full, in-depth scholarly treatment, something not previously done. Rudy’s book was a pioneer work of synthesis and much original research.

Prior to Blacks in Gold Rush California, Lapp had written for a fine-printing book club an account of the most celebrated and notorious fugitive slave episode in California, the case of Archie Lee. Rudy’s colleagues told him that the Archie Lee story should “go prime time”: it had a sympathetic hero, drama, interesting characters, an escape, plot twists, and a last-minute rescue – the stuff that the entertainment industry thrives on. Lapp had no large thesis in this 67-page book; it was just a good story well told that he lets the reader draw conclusions from.

Rudy also contributed Afro-Americans in California to a multi-title California history series, taking the story of the California black experience to a longer time line.

Even before these books emerged, Rudy had already established his creds in academia with his articles in the Journal of Negro History and the California Historical Quarterly. He would also have book reviews, and contributions to the Dictionary of Negro Biography, the Reader’s Encyclopedia to the American West, and American National Biography.

Growing up in Chicago in the 20’s and 30’s

How did Rudy come to be a teacher and historian? The answer might lie on his growing up in Chicago’s diverse West and North West Sides during the 1920s and the Great Depression in a secular Jewish family which loved to discuss current events and social issues. (One of Rudy’s high school pals who became a life-time friend was the Nobel laureate in literature Saul Bellow.) Rudy attended YMCA College (later Roosevelt University) in the Depression and taught at community centers flourishing under the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal. He also participated in demonstrations supporting the Scottsboro Boys, the defendants in a famous Southern trial that aroused civil-rights activism.

World War II experiences

When the U. S. entered World War II in December 1941, Rudy was soon drafted into the army, despite his lifelong deafness in one ear. Before he was sent overseas, he married Patricia Teeling and they were married 65 years when he died. (Pat Lapp herself passed in January this year.) The U. S. Army transported him to England where he was stationed at an airbase in Berkshire. There he was assigned to do cultural and educational programs for base personnel. This wartime assignment as well as his pre-war teaching experience would prefigure his future life as a college professor. His encounters during the war with racist fellow servicemen would reinforce his role later as an activist.

Graduate school at Berkeley

Returning to Chicago after the war to complete college on the GI Bill and to work, Rudy would soon heed the call of academia, and he and Patricia left for Berkeley and graduate studies. His mentor at Cal was the renowned Civil War and Reconstruction historian Kenneth M. Stampp. Stampp directed Rudy’s research into the society of the pre-Civil War South. Lapp’s probing of the sources would, of course, turn up material on the condition of blacks at that time.

When Rudy came to CSM, it was not only to teach American history, but also to assist Dr. Frank Stanger, a longtime faculty member who was instrumental in the founding of the local historical association. Rudy would both be working with the association’s museum and be teaching classes at CSM. In time this dual responsibility would end and Rudy would be full-time in the classroom.

Anti-war activism at CSM

Rudy, who had supported civil rights causes in the past, became involved in the activism of the 1960s and 1970s involving the Vietnam War. At one point CSM’s Academic Senate sent Rudy to Washington in May 1970 to join the protests against the U. S. incursion into Cambodia during that conflict. In Mitchell Postel’s account of San Mateo in the 1960s, those years almost become the “Lapp Years” in San Mateo because of the prominence Postel gave to Rudy’s role in the discourse and manifestations at the time.

Pioneering Black history class

While Rudy’s output as a published writer had given him recognition in the field, his chief contribution to the discipline of history was as a teacher of history. One of his singular efforts in the teaching of history at CSM was his “The South and the Negro in American History,” which was in the schedule in 1959. This course appears to be the first Black history course given at a California community or junior college. Within a few years the class became “Afro-American History,” a course other institutions would similarly offer, but CSM is apparently the pioneer.

Former students follow historical paths

Rudy, who retired in 1983, but continued to teach part-time for a few years more, possibly had taught at least 14,000 students, one of whom was Claire Mack, who became the first Black mayor of San Mateo and is a retired KCSM staff member. Also among his students are retired athletics dean Gary Dilley, San Mateo County Historical Association President and Executive Director Mitchell Postel, and Stephen Petty, humanities professor at Santa Rosa Junior College and a colleague of Rudy’s late artist brother Maurice. (Petty was also the son of a CSM faculty member, Claude Petty).

Let Mitch Postel provide the concluding comment on Rudy as a teacher: “Agree with him or not …, his classes were quite lively. No student could sleep through one of them.” From Rudy’s class, Postel says, “You came away with a new thirst for knowledge, and, in my opinion, that is what higher education is all about.”